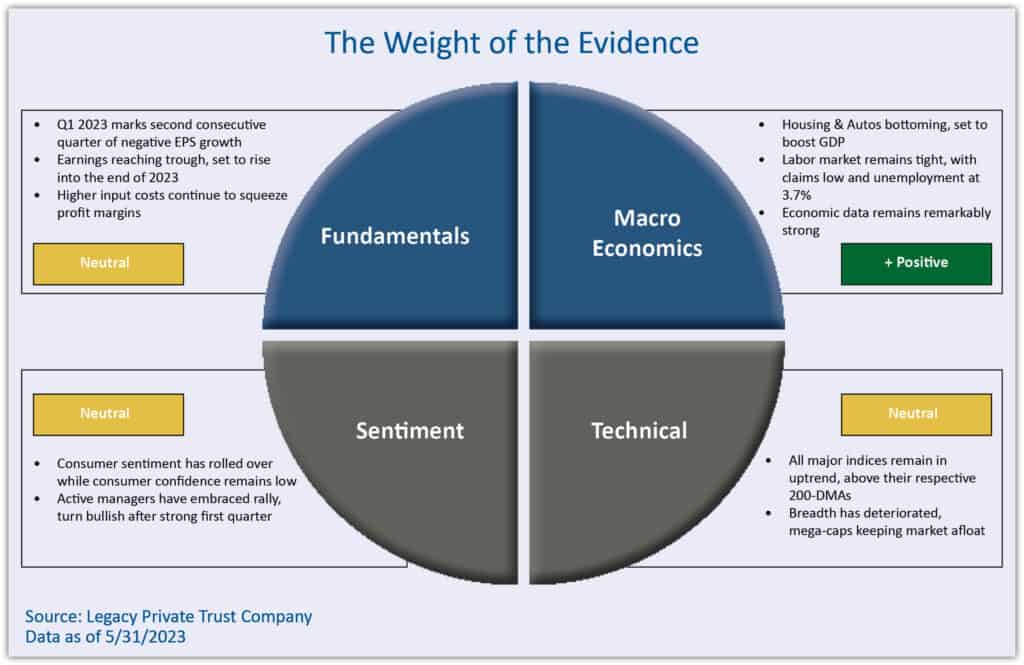

As the curtain rises on the second half of the year, the economy’s growth engine is still firing on all cylinders. Consumers, the main growth driver, are keeping their wallets open, jobs are still being created at a healthy pace, workers are getting decent raises, high food and energy prices have eased, and the AI revolution is boosting investment spending. Even the freefall in the housing industry appears to have stabilized and is now starting to move higher, as housing starts soared to the highest level in over a year in May, and sales of new single-family homes are rising again. This does not look like an economy on the cusp of a recession, a prospect that the consensus of economists believed was just around the corner most of the last year.

With most economic data coming in stronger than expected, that consensus is fraying at the edges. Economists are pushing back the timing of the predicted recession to later this year or early in 2024. The Federal Reserve adjusted its forecast in the latest Summary of Economic Projections. In March, they predicted the economy would only grow by 0.4% in 2023, which implicitly assumed GDP would contract in the year’s second half. However, at their June policy-setting meeting, they boosted that forecast to a 1.0% growth rate, which assumes the expansion would continue until at least 2024.

That said, the central bank’s upgraded forecast didn’t stop it from skipping a rate hike at the June 14-15 meeting after ten consecutive increases dating back to March 2022 aimed at taming inflation. It’s unclear if the Fed paused because they believed another rate hike would have triggered a bad reaction in the financial markets. After all, the Fed had telegraphed that they would skip a rate hike well in advance, and traditionally they do not like to upend market expectations. But they also do not want to convey a different message – that they are abandoning the inflation fight. Hence, policymakers warned that a pause does not mean a stop, predicting two more quarter-point rate increases by year-end. The question is whether they will continue tightening, which economists believe would almost surely cause a recession.

Making the Hawkish Case

At the press conference following the June 15 policy meeting, Fed Chair Powell noted that the next gathering on July 26 would be “live,” raising the prospect that another rate hike would occur at that meeting. In the so-called “dot plots” that depict predictions of the 19 voting members on the policy-setting committee, most expected two more increases this year, which would lift the federal funds rate to 5.625% from the current 5.125%. The rate has not been that high since January 2001, a month before the first recession of the millennium got underway.

More important than the level of rates is how rapidly they have increased. The climb from near zero in March of 2022 is the swiftest since the early 1980s when the Fed jacked up the rate from under 10% to 20% in a comparable period. The Fed wants to avoid repeating the mistake it made during that earlier period when it prematurely took its foot off the brakes and let inflation fester, which nourished expectations that high inflation was a normal feature of the economy. It took several rounds of aggressive tightening and a severe recession in the early 80s to finally break the back of inflation expectations.

No one expects the Fed to be as aggressive as it was, if only because it strives to tame a 5% inflation rate rather than the sky-high 12% that prevailed then. What’s more, unlike in the 1980s, inflation expectations have remained tempered, leaving the Fed the flexibility to pause rate hikes without risking its inflation-fighting credibility. By pausing, policymakers are also giving themselves time to assess the impact of previous rate hikes on the economy.

Mixed Results

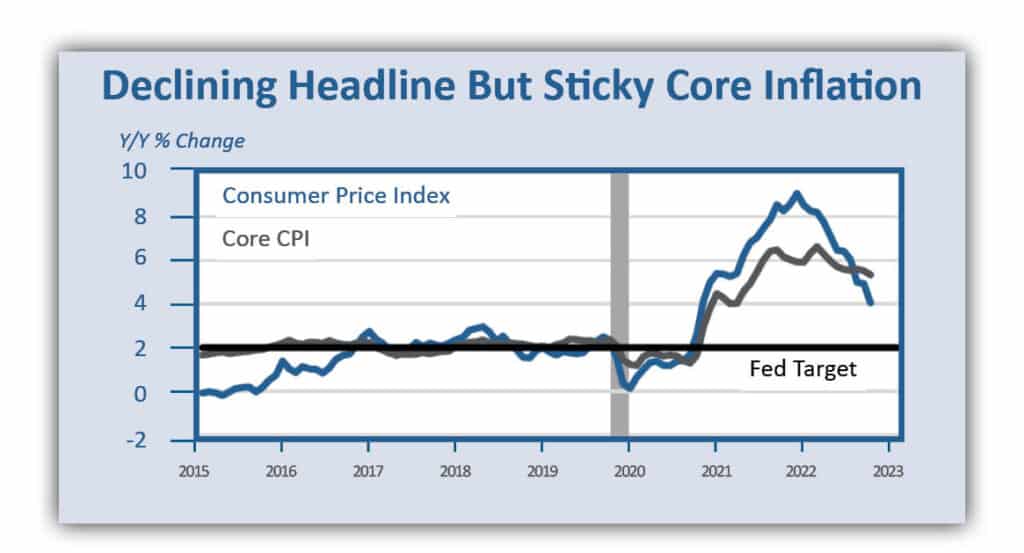

So far, conditions have held up better than expected, raising the prospect that the Fed can tame inflation without causing a recession – the so-called ‘soft landing’ they set out to achieve at the start of the rate-hiking cycle. But it’s far too early to declare victory on inflation. True, consumer price increases have eased considerably this year; the annual increase in the consumer price index has slowed for eleven consecutive months, from 9% last June to 4.1% in May. But plunging energy prices and slower increases in food prices accounted for much of that slide and did not reflect the underlying inflation trend.

When adjusted for the price volatility associated with these items, the slowdown in inflation is far less impressive. The core CPI, which excludes those items, has slipped to 5.3% in May from a peak of 6.6% last September and remains far above its pre-pandemic trend and the Fed’s 2% target. True, just as the plunge in the headline falling oil prices heavily influenced CPI, so too is the core CPI being propped up by shelter prices–primarily rents–which the Fed has little control over. For that reason, they are laser-focused on the prices of non-housing services – including restaurants, hotels, pet grooming, airfares, and medical fees — linked to labor costs and job market trends, which the Fed can influence through its interest rate decisions.

The sticky inflation of this so-called “super-core” group of items keeps the Fed biased towards further rate increases. In May, super-core CPI increased 4.6% from the year before, slower than the 6.5% peak reached last September but still far too hot. The Fed believes that the still-tight labor market, upward wage pressures, and excess savings from covid transfer payments are the primary reasons these prices are not cooling fast enough. That is also why the Fed will not remove its foot from the monetary brakes until more cracks in the labor market appear.

How Much Further?

Some believe it would be virtually impossible to wrestle inflation down to 2% without causing a serious recession. They argue that the Fed should be flexible and adjust the target upward, say to 3%, which is within sight and something that most people could live with. However, the central bank understandably fears revising its target upward as that could undercut its credibility. It could also evoke the rampant inflation period of the 1970s and early 1980s, when policymakers prematurely took their foot off the brakes to avoid a recession, allowing inflation expectations to gain traction that spurred even harsher tightening moves later.

The problem is that finding the magical interest rate that would restore inflation to the 2% target without inducing a recession is a challenging task. Indeed, the Fed has a history of overshooting the mark, hiking rates until it is too late and something breaks. One reason is that the economy reacts to rate increases with a lag, and it is virtually impossible to predict when that breaking point will be reached. In past cycles, it has taken as long as 15 months for the economy to enter a recession after the last rate hike of a tightening cycle. One exception when the Fed successfully tamed inflation while guiding the economy into a soft landing was in mid-1995. But then inflation peaked at 3 ¼%, and the Fed’s objective was to stop it from rising, not bring it down, as is currently the case.

To be fair, the Fed recognizes the lags involved and is adjusting its moves accordingly. The speediest phase of the tightening cycle occurred last year when it hiked rates by 50 or 75 basis points at each meeting after realizing it waited too long to start the inflation fight. The three increases this year were scaled back to quarter-point rises. Unless inflation suddenly reaccelerates, the next increase, if it does occur, is likely to be no larger. While the median forecast of Fed officials is for two more rate increases this year, investors are betting that one more hike at their July meeting will be the last.

Staying The Course

Based on recent comments by Fed officials, most notably Chair Powell in his semiannual testimony before Congress on June 21, the central bank is likely to err on the side of keeping rates higher and for longer than the financial markets anticipate. Powell made it abundantly clear that he doesn’t think the Fed has done enough to nudge inflation towards its 2% target. However, there is a real risk that the Fed will once again overshoot their mark if they follow through with two more hikes.

While core service inflation is likely to remain sticky, thanks to a tight labor market, this core group of items accounts for less than 30% of the consumer price index. By focusing on this narrow component, the Fed would apply a blunt instrument – interest rates – that could generate more job losses than necessary. Most other prices have already cooled considerably as supply-chain snags that caused shortages during the pandemic have cleared up, and households are becoming more price-conscious as their excess savings have dwindled. Importantly, housing inflation, which accounts for an outsize 34% of the core CPI, is poised to ease in coming months as rents on new leases are seeing much smaller increases than earlier in the year. Used car prices have also come off their highs and should put less upward pressure on core inflation over the next quarter. Lower core CPI prints are coming.

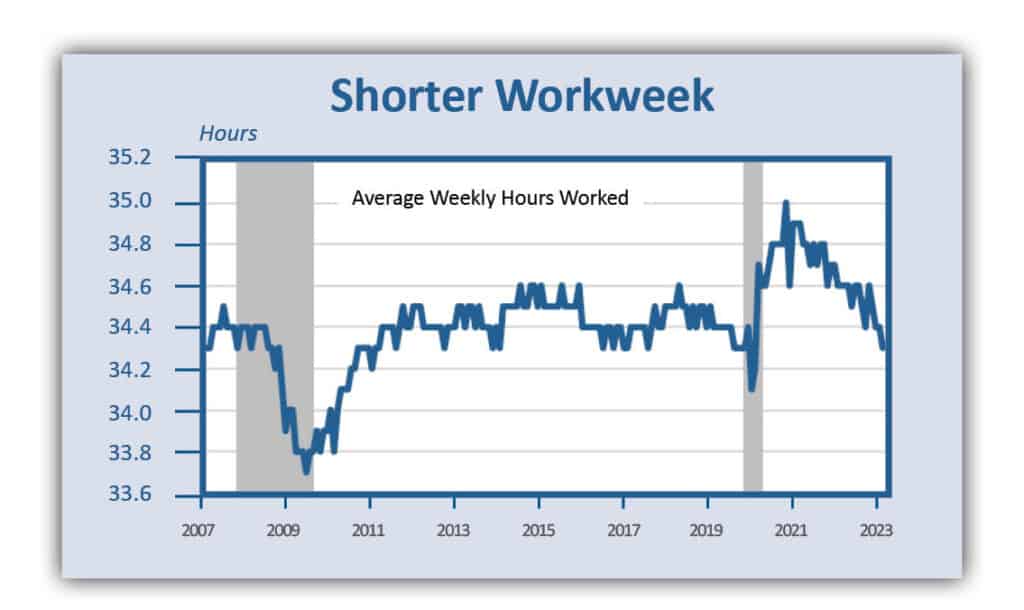

Meanwhile, cracks are appearing in the job market; new claims for unemployment benefits, while still low, are rising, companies are posting fewer job openings, and workers are less willing to quit, seeing fewer lucrative opportunities elsewhere. The unemployment rate is still at a historically low 3.7%. But employers are cutting worker hours instead of reducing payrolls in the face of slowing growth. They are hoarding labor to avoid the rehiring difficulties they encountered during the post-pandemic recovery. However, the lagged effects of the Fed’s tightening will soon bite more deeply into revenue growth, prompting companies to take a harder line on staffing needs.

Simply put, if the Fed continues to raise rates in response to backward-looking inflation and economic data – which they seem poised to do – the risk that they turn a prospective soft landing into a hard downturn is greatly enhanced. One more rate hike probably won’t make much difference, but two might be the straw that breaks the economy’s back. Policymakers are prepared to accept a mild recession, including a rise in the unemployment rate to 4.5%. That would still be low by historical standards. Still, once employers are convinced the Fed will induce a recession, they will probably abandon the hoarding instinct and send more workers onto the unemployment lines than policymakers anticipate. Then, the inflation fight would be conquered but replaced by a new battle – combating a deep recession and deflation.

If you are a Legacy client and have questions, please do not hesitate to contact your Legacy advisor. If you are not a Legacy client and are interested in learning more about our approach to personalized wealth management, please contact us at 920.967.5020 or connect@lptrust.com.

The information contained herein is for informational purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation or advice. Any opinions are those of Legacy Private Trust Company only and represent our current analysis and judgment and are subject to change. Actual results, performance, or events may differ based on changing circumstances. No statements contained herein constitute any type of guarantee, nor are they a substitute for professional legal, tax, or other specialized advice.